Passive Skills in Published Adventures

A lot of the theory here suggests that passive skill checks should be avoided as they only serve to disambiguate when meaningful failures or successes are at hand. But one other way passive skills can be useful is when running published adventures. In pre-written modules, most skill-based encounter elements are assigned DCs by the module writers. But they have no idea what the party composition or character builds are going to be so they can’t tune encounters accordingly.

Comparing intended DCs against your players’ passive skills is a good way to determine whether an encounter feature represents a meaningful challenge or not. If a party’s rogue has Passive Perception of 17 and a secret door in a room requires a Wisdom (Perception) check against a DC 10, it’s safe to assume that secret was designed to be discovered (it’s an Easy task on the DC chart) and as soon as the rogue walks in, they notice the secret door, no roll required.

When to Roll

A conversation happened recently on the group Discord #dungeons-and-dragons channel where the idea of passive abilities and appropriate use of dice rolling was discussed. The essence of it was that passive abilities—including the most common ones, Perception and Investigation—seem a little dubious in their overall application. Which dovetailed pretty naturally into a conversation about when DMs should call for dice rolls (ostensibly as opposed to using passive abilities, but also just in general).

The upshot is that dice should only be rolled when there is a meaningful chance of failure or success. Forcing players to make rolls against DCs of 30+ at second level, for example, would not suggest a meaningful chance of success since even on a natural 20 few characters have bonuses sufficient to achieve that total. Likewise, rolling for a character to walk down a flight of stairs with no other mitigating circumstance just on the off chance they roll a 1 is not just cumbersome but potentially cruel. Critical failures should be expected roughly 5% of the time, which means you’d have to assume a given character falls down flights of stairs that often for a roll like that to make any kind of sense. This is explicitly stated in the Dungeon Master’s Guide (the DMG actually specifies, “Only call for a roll if there is a meaningful consequence for failure (pg 237)” but, as discussed below, dice can represent positive change in status quo without an associated negative change as well, which is why we describe both here), but sometimes gets overlooked.

The upshot is that dice should only be rolled when there is a meaningful chance of failure or success. Forcing players to make rolls against DCs of 30+ at second level, for example, would not suggest a meaningful chance of success since even on a natural 20 few characters have bonuses sufficient to achieve that total. Likewise, rolling for a character to walk down a flight of stairs with no other mitigating circumstance just on the off chance they roll a 1 is not just cumbersome but potentially cruel. Critical failures should be expected roughly 5% of the time, which means you’d have to assume a given character falls down flights of stairs that often for a roll like that to make any kind of sense. This is explicitly stated in the Dungeon Master’s Guide (the DMG actually specifies, “Only call for a roll if there is a meaningful consequence for failure (pg 237)” but, as discussed below, dice can represent positive change in status quo without an associated negative change as well, which is why we describe both here), but sometimes gets overlooked.

“Dice should only be rolled when there is a meaningful chance of failure or success.”

But we do need to be clear about the work the word “meaningful” is performing in that sentence. Part of what designates a potential outcome as meaningful is that success indicates identifiable benefit while failure carries obvious repercussions. We can shortcut this with the term “associated cost.”

Associated Cost

The cost of failure and the reciprocal benefit of success should be, at least abstractly, quantifiable. And, less abstractly, it should be something that has plot implications. Role-playing games are storytelling activities, after all, so quantities matter when they develop the plot in one way or another. To a certain extent, every minute activity could be given a quantifiable associated cost. Older role-playing game systems I’ve used had mechanics such as speech or language skills. We used to joke that when a person misused a word or stuttered trying to get a sentence out that they had “failed their speech roll.” By the reason those systems didn’t intend for players to roll dice each and every time their character was trying to ask a shopkeeper for a price or a random passerby for directions to the dragon’s cave is because the associated cost for that kind of failure would be a nearly imperceptible level of embarrassment, maybe, and a couple milliseconds worth of attempting to say what they were trying to say a second time, possibly more slowly. In terms of an RPG, that kind of failure would almost never have genuine plot implications.

It is possible—maybe even easy—to imagine scenarios where the cost for such activities is elevated to a level where there would be plot implications. If the item the character were asking the shopkeeper about was a family heirloom that had been stolen and they presumed was lost forever, being able to inquire about its cost in a nonchalant manner might matter significantly, especially if they were hoping to maneuver the conversation into a series of questions about how it had wound up in the shop. The associated cost in that case might be an elevated level of suspicion on the shopkeeper’s part which might cause them to drive the price up out of the character’s financial range. Or the shopkeeper might have been a thief prior to settling down and a crack in the character’s voice or an eagerness that belied the character’s attachment to the item might tip the shopkeeper off that this might be the item’s rightful owner. In those cases the associated cost has plot implications. If the character can’t buy the item outright or the shopkeeper feels threatened, it could change the course of both of their days (or lives!). D&D doesn’t have a speech skill, but a Charisma skill check could certainly be in order (perhaps Deception or Performance) to ensure that the character’s desired outcome comes to pass.

Often the associated cost for a called die roll would be as simple as time, but again, only if the loss of that time were to have real implications on the plot.

Meaningful Success and Passive Skills

While it’s fairly easy to identify meaningful consequences for failure when applying the plot significance guideline, it’s not always as easy to define what matters plot-wise when it comes to success. Imagine a group of adventurers exploring a dungeon and one room of the dungeon there is a secret door. The door leads to an otherwise unremarkable shortcut which skips them past a couple of occupied rooms or corridors between their current location and the stairs leading down to the dungeon’s lower level. In this scenario, if a PC misses the DC 15 on their investigation check, does that have plot implications? Potentially, depending on how powerful the creatures inhabiting the intermediary rooms might be, or how recently the party has rested. Or maybe it doesn’t matter at all. In some cases it may matter how a DM chooses to contextualize this potential outcome. Is rolling too low on a Wisdom (Investigation) check to find a secret door the PCs had no idea would be there a failure to locate the secret passage or simply a missed opportunity for success? Failures by their nature have inverse successful outcomes, but I don’t know that you can say that every potential success has an associated failure.

Present Status Entropy

The reason for this is, for lack of better term, present status entropy. If a character standing in front of an altar has full hit points, no levels of exhaustion, a purse with X pieces of gold in it, and their magic +1 sword of blasting, that could be considered their present status (general condition: good). If they fail to spot a stalactite dropping from the ceiling to their head, they end up with fewer hit points and their status has changed (general condition: fair, perhaps). If they fail to stop the invisible imp from swiping their coin purse, they are now poorer than they were. But conversely, if they fail to remember the magic words that could allow the altar to activate and giving them a blessing of divinity, there has been no entropy to their present status. Everything is the same. Technically their status could have gone from good to fantastic, but they don’t necessarily know that. Barring any entropy on their condition, a “failed” Intelligence (Religion) check is perhaps not a failure at all.

This applies in reverse as well. If a character is chatting with a shopkeeper and she decides to flirt with them to try and get better prices, a Charisma check might change the present status of their relationship to something more positive. But if the check fails, perhaps shopkeeper fails to pick up on the vibes or simply ignores it (“Sorry you’re not my type”) and there is no entropy applied in either direction.

In some cases I think this is one area where passive skills have their uses. If a player is forced to roll for a check that bears no status entropy implications but does bear plot implications, the act of rolling itself gives the impression of status entropy. If they roll a 14 and the DM just shrugs or nods and says nothing else, the player’s character may have not changed status, but the player themselves might! They may even want to try the roll again (thinking, maybe something other than nothing will happen this time). A passive skill check could have solved that issue by allowing the DM to describe the blessing if they approached the altar with a passive INT score of 17 (and yes, I know active skills aren’t supposed to be lower than passive skills).

What Causes Success or Failure?

The other thing to bear in mind is that rolls are abstractions of player characters’ actions and abilities. Many DMs, including myself, have often stretched credulity when describing failure in particular. “The Ranger with decades of training and experience, using the bow their father gave them when they were less than three years old, draws back a nocked arrow… and drops the arrow into the dirt. No damage.”

A recent discussion on an online message board went into this principle in detail suggesting that failures for the most part should only be attributed directly to the character if it:

- Fits the character profile and backstory

- Intentionally suits the narrative (should be used sparingly)

- Is necessary for levity (but not at the expense of player/character engagement)

In short, DMs should strive to make sure their PCs are competent and above all cool, rather than bumbling doofuses unless the player wants and intends for their character to be as such.

To this end, failures should far more frequently be attributed to external factors. Trained assassins who can mystically blend with the shadows shouldn’t let out farts that give away their positions, rather a squeaky floorboard or an unexpected change in the guard’s patrol pattern can be the cause of the ‘failure’.

Conversely, success should almost always be attributed to and described as competence rather than luck or happenstance unless the odds of success were notably long. Generally speaking I’d say luck should never be a narrative factor unless the expected roll is at least two levels off from the task difficulty (e.g. a player with a -2 ability modifier rolling on a d20 should statistically expect to roll a 9 which means tasks they can reasonably expect to accomplish without a stroke of good fortune would be Very Easy and Easy tasks; for Hard or above tasks which require rolls of 17+, those successes can be attributed to luck).

The Nature of Failure

Another element discussed in Discord was the nature of failure. Because success/failure as a binary game mechanic occurs within the framework of a narrative, the specifics—including the associated costs—are handled via the DM. In D&D 5e, there are no mechanics governing the interactions between player roll and DM interpretation. This leads to the case described above where causes of success or failures can have general guidelines to avoid player dissatisfaction.

But there is another element beyond just the underlying cause for a given outcome and that is the overall effect of that same outcome. Take the following two examples of a PC failing to make a Strength (Athletics) check to climb and then failing a Dexterity (Acrobatics) check to recover from the fall:

“The Barbarian climbs the cliff face with the stolen idol strapped to her back. Halfway up, she slips and falls. She reaches out to grasp a ledge as she plummets, but her fingers barely miss and she lands with a hard thud right in the ring of the angry goblins below.”

Or:

“The Barbarian climbs the cliff face with the stolen idol strapped to her back. Halfway up, a handhold that looked sturdy crumbles under the extra weight of the stone idol. Scrabbling for a new handhold on the way down, she can’t find purchase until the rope holding the idol catches on a sharp outcropping, slowing her enough to hold on, a mere ten feet above the angry goblins below. As she grits her teeth, barely clinging to the rock, she feels the rope start to unravel, its integrity compromised.”

Technically both scenarios accomplish the same game and plot function. The associated cost was always falling damage and a potential encounter with the pursuing goblins, but associated cost does not mean required outcome. Failure should generally lead to more decisions, not less. In the first example, the Barbarian’s primary options are to fight (now with fewer starting hit points due to the fall) or try to talk her way out of it. In the second example, the Barbarian’s options are wider: let go, taking less falling damage or perhaps triggering a check to land more gracefully (either way initiating the same primary options as the previous example); try to secure her grip on the cliff; try to secure the rope or grip the idol tighter. In this case the options don’t even eliminate the core options from the first outcome, which makes for more dynamic games. As an ancillary benefit, the second example still showcases the Barbarian as strong and capable rather than just an oaf who couldn’t climb up a wall, but competence doesn’t always trump circumstance.

In a lot of ways this is the essence of the “yes, and…” nature of quality DMing.

Associated Cost Vs Passive Skills

The rules as written, particularly the passive skill rules and the 10/20 rule, highlight the use of skill checks when there are no associated costs. If the PCs have murdered the reclusive sage in his home, no one else is in the vicinity, and there is no time pressure to locate it, calling for a Wisdom (Perception) or Intelligence (Investigation) roll to find the forbidden prophecy scroll in the sage’s library is pointless.

Except, there is an associated cost, isn’t there? Whether there is time pressure or not, it does take time to execute a task. Passive checks are meant to approximate repeated attempts but the rules are mum about what that means in practice. Many DMs have formulas to derive time from Passive ability scores or based on the target DCs, but in the end it’s up to the DM to decide the associated cost for Passive skill.

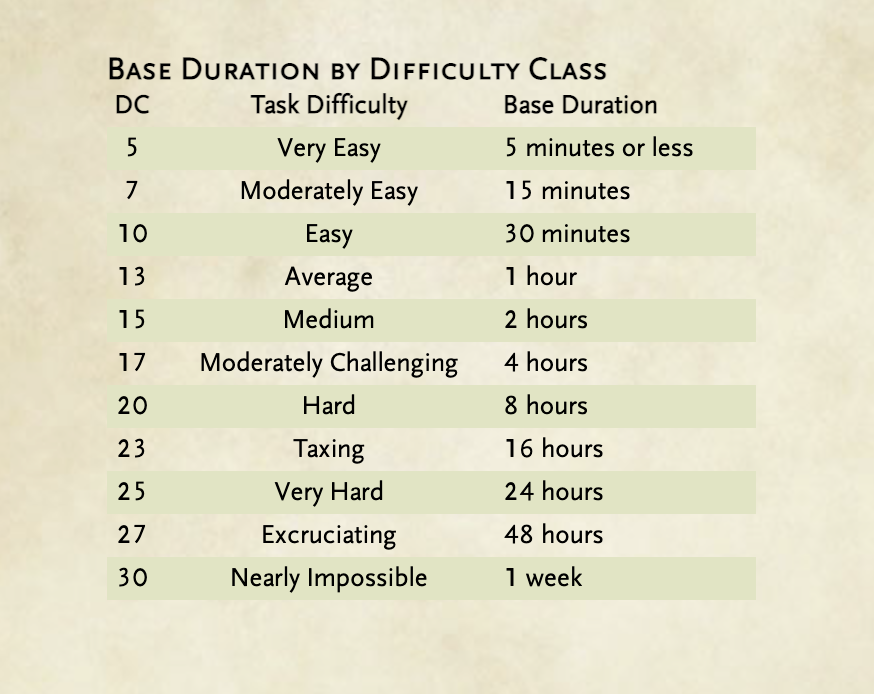

Applying time variance is a constant concern for DMs, even when time is not factored into the encounter’s mechanics. One possible abstraction would be to convert the DC into base times:

In this case the standard difficulty classes have been expanded upon a bit to better show the progression as DC increases. The calculations are quasi-logarithmic and it should be noted that applying the Help action, which typically confers advantage on a check, in this case decreases the DC by one class level per helper.

If you imagine finding a literal needle in a haystack, the DC of 30 represents a full week of work (that is to say, 168 hours) which cannot be done without requisite breaks. Devoting 10 hours per day to the task would then take well over two and a half weeks of calendar time, working at eight hours per day would take a full three weeks. But with one helper, the job duration is significantly reduced to 48 hours or four to six days working time. With five characters working together, they can find the needle in a mere four hours.

And this is assuming a passive score for an applicable skill at the base DC level for all helpers. If finding the sage’s scroll from the earlier example was a DC 17, a character with a passive Intelligence (Investigation) of 18 can find the scroll after four hours of searching, but they can’t be aided by a character with a passive Investigation score of 12; they’re just not helping enough to make a difference.